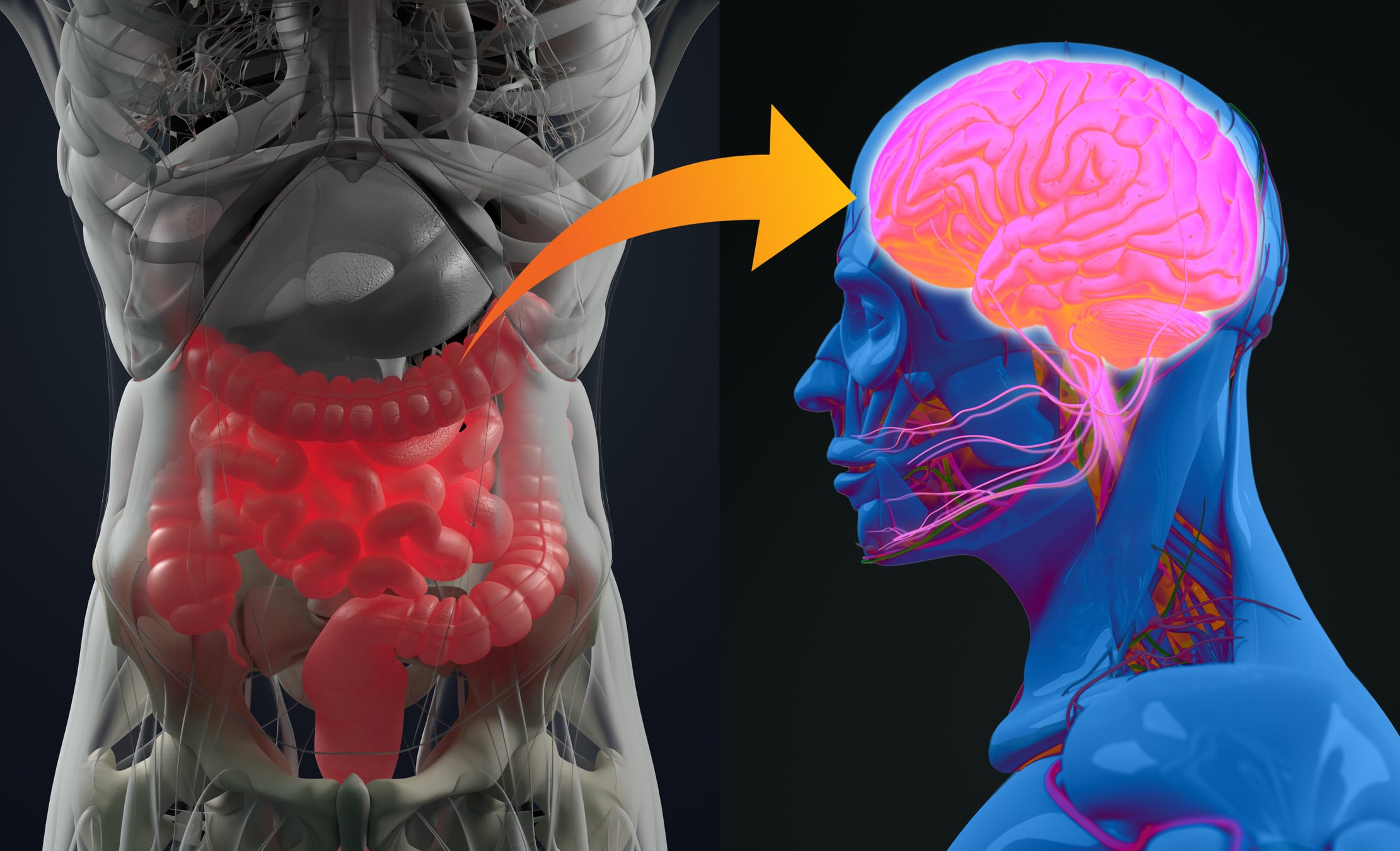

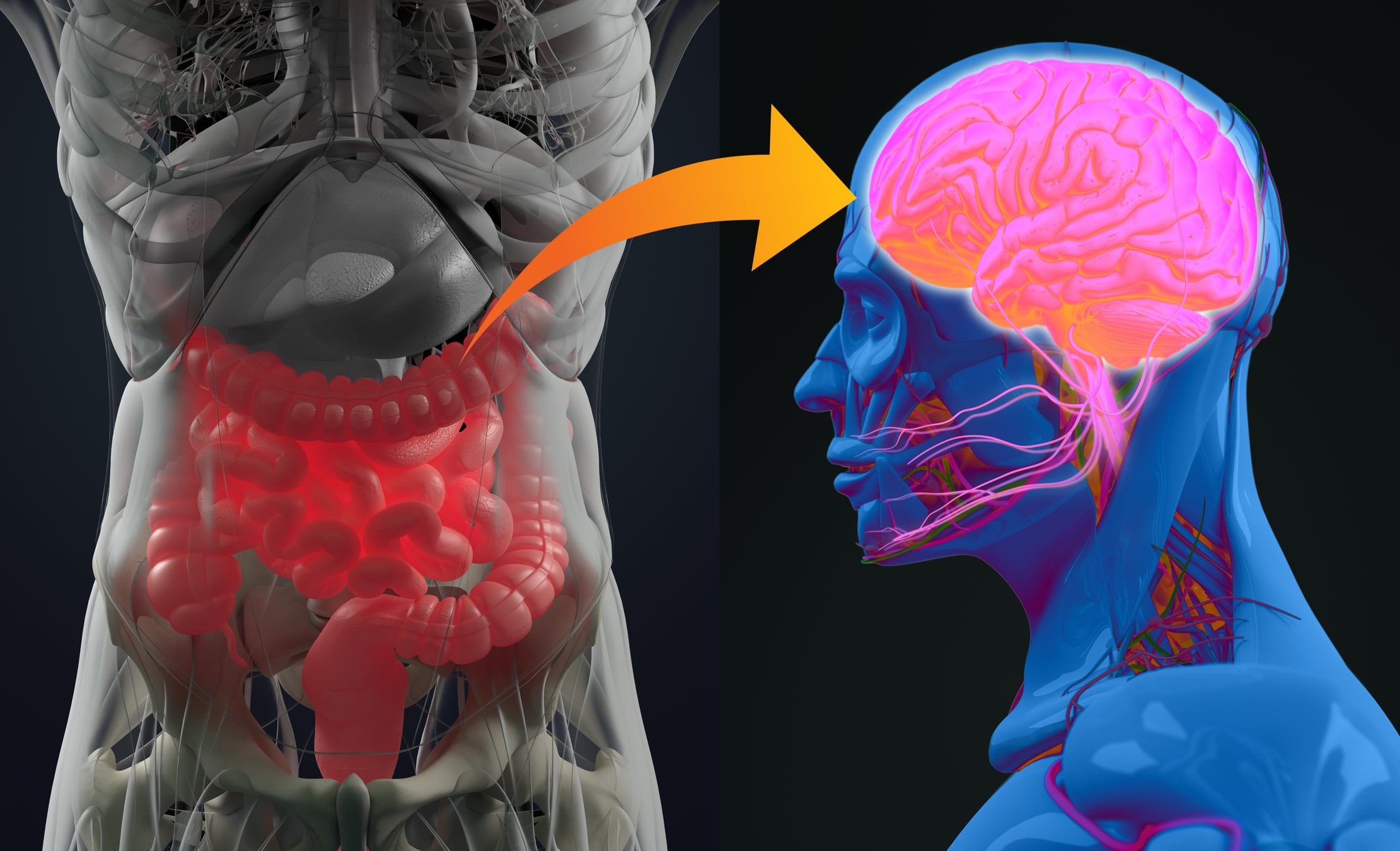

The gut–brain axis is a bidirectional link which allows the gut microbiota to act as a potential therapeutic target for psychiatric disorders. As such, certain probiotics have been identified as “psychobiotics” as they can bring health benefits to patients with mental illness, such as insomnia.

Sleep is closely related to the gastrointestinal microbiota. Factors such as sleep deprivation, working night shifts, and circadian disorders can change the structure of gastrointestinal microbiota and circadian gene expression. Some research has shown that supplemental probiotics can enhance sleep quality or relieve stress, but most only measured sleep quality using subjective questionnaires.

Preclinical studies have shown that Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 can increase levels of dopamine and serotonin in the brain to ameliorate psychiatric symptoms in rodents. Therefore, the authors of the current study hypothesised that PS128 can enhance sleep quality by ameliorating mood and reducing cortical excitation in self-reported insomniacs.

The current study aimed to determine (i) whether there is a relationship between PS128 and depressive symptoms or anxiety, (ii) whether PS128 could regulate the ANS by reducing the sympathetic nervous system and increasing the parasympathetic nervous system during sleep, (iii) whether PS128 could improve sleep quality by increasing sleep efficiency, maintaining sleep duration, and decreasing sleep latency, and (iv) whether the change in sleep quality is related to mood.

In addition to subjective measures, the research used miniature polysomnography (PSG), which provides the most direct objective assessment of sleep architecture.

The study

This was a randomised, double-blind, parallel, placebo-controlled pilot trial involving 40 otherwise healthy self-reported insomniacs (aged 20-40). During the screening period, sex, age, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (BP), health habits, and medical history of all participants were recorded. Participants completed a sleep log for one week to record their daily schedules and sleep habits.

They wore an electrocardiogram (ECG) patch all day to objectively measure their sleep-wake cycle, and an oximeter during sleep to exclude sleep apnea. All participants were evaluated by miniature-PSG for two nights, to objectively assess their sleep quality.

After the above evaluations, participants started taking two capsules of either PS128 or placebo after dinner for 30 days. On the 15th and 30th days after they started taking the capsules, participants were evaluated by miniature-PSG.

On the day of the miniature-PSG recording, the visual analogue scale (VAS) was used to assess the relaxation level, fatigue level, and sleep quality. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) were used to evaluate subjective sleep quality and insomnia severity.

Daytime sleepiness was measured using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), depression was assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), anxiety levels were assessed using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and the State-Trait Anxiety Index (STAI), and circadian rhythm was assessed using the Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ).

Results

The resulting data suggests that participants in the PS128 group experienced fewer depressive symptoms and fatigue, less frequent awakening and arousal, and decreased high-frequency brain wave activity. The objective parameters indicated more stable sleep in the PS128 group than in the control group. PS128 was not found to have a significant effect on ANS function.

Research background

These findings are similar to Armitage’s results, in which insomniacs reporting poor sleep were more depressed and had higher alpha wave levels than healthy participants. Those experiencing less stress also had higher delta wave levels. Moreover, BDI-II and BAI scores in the PS128 group improved throughout the study period, suggesting prolonged amelioration of depressive symptoms and anxiety with regular consumption of PS128.

PS128 has shown some beneficial effects on mental disorders, such as the autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and has been reported to ameliorate anxiety, hyperactivity, impulse, and opposition/defiance behaviors. Furthermore, it may have a potential benefit for mood disorders, as the main finding of this study suggested that PS128 may be able to reduce depressive symptoms in insomniacs, which is consistent with previous studies on PS128.

Although the study did not test biochemical markers, a previous study on PS128 found that its use can increase dopamine and serotonin levels in the brain of mice. These two neurotransmitters are classified as excitatory neurotransmitters in the field of sleep medicine - they may inhibit GABA neurons and activate the cortex, causing sleep disturbance. However, the specific role of serotonin on sleep is still unclear. Preclinical studies have shown that PS128 adjusts brain dopamine levels and enhances exercise performance in triathletes. The authors of the current study therefore hypothesise that by taking PS128, participants in the intervention group may have avoided fatigue, as the psychobiotic modulated their dopamine levels.

A previous study investigating the effects of Lactobacillus casei Shirota on 132 subjects showed that probiotics only affect those whose mood was initially poor. Thus, the current study analysed the correlation between changes in objective parameters and BDI-II scores. We found that when depressive symptoms were alleviated in the PS128 group, beta power percentage and alpha power percentage were reduced, while delta power percentage was increased. In other words, those who respond to PS128 may have less cortical excitation and deep sleep.

This study has several limitations. First, intestinal microbiome analysis was not carried out. Second, the small sample size might not be able to provide strong statistical evidence to explain the results. The lack of a cross-over design could be a serious limitation when the sample size was so limited. Third, the results may not be generalizable to other populations because of the small sample size. Fourth, the EEG analysis improperly included sigma activity (12–15 Hz), which mostly corresponds to sleep spindles within the alpha and beta power. Fifth, the researchers did not restrict or record the diet of the participants throughout the intervention - they only advised the subjects not to consume caffeine on the day of the miniature-PSG measurement. Finally, participants were instructed to take the capsule after dinner, and the timing of this varied among the participates.

Insomnia and depression

Up to 40% of insomniacs also suffer from psychiatric disorders, with depression and anxiety being the most common. Sleeping pills are prescribed to millions of patients every year, but common negative side effects include addiction, fatigue, and long-term alterations in brainwave activity. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is an effective non-medical treatment but it is time-consuming, complicated, and the premature dropout rate of CBT-I is approximately 40%.

Although the exact cause of insomnia is unknown, many studies support the hyper-arousal theory, which states that insomnia results from a dysfunctional hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. The HPA axis plays a central role in the stress response, and is also involved in digestion, endocrine activity, immunity, and mood.

Evidence shows that during sleep, insomniacs have increased high-frequency electroencephalogram (EEG) activity, adrenocorticotropic hormone (which stimulates cortisol release) levels, heart rates, and autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity compared to healthy people. Moreover, neurotransmitters also seem to play a role in insomnia.

Insomniacs often have an imbalance of neurotransmitters that drive the sleep-wake cycle. These include those that induce sleep, such as gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), adenosine, and melatonin, and those that promote waking, such as noradrenaline, serotonin, acetylcholine, orexin, and dopamine.

Source: Nutrients

Ho, Y.-T., Tsai, Y.-C., Kuo, T.B.J., and Yang, C.C.H.

"Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 on Depressive Symptoms and Sleep Quality in Self-Reported Insomniacs: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Trial"

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13082820 (registering DOI)