Loss of appetite, or anorexia, is estimated to affect 27% of those aged over 65 years and is a major component in the development of sarcopenia, a progressive skeletal muscle disorder involving the accelerated loss of muscle mass and function.

Loss of appetite in older age is due to multiple underlying determinants as part of the ageing process including alterations in mechanical and neuroendocrine functioning of the gut. Microbial metabolites, including SCFAs, BCAAs, and peptidoglycans, are critical to enterocyte function, including interacting with enteroendocrine cells in the gut wall. The composition of the gut microbiome is known to change with age and health status and alterations in its composition have been associated with frailty, anabolic resistance, and skeletal muscle function.

The primary objective of this study was to explore if there was a difference in the composition of the gut microbiota between community dwelling people aged 65 years and older reporting good or poor appetite.

The researchers used an online questionnaire sent to members of TwinsUK, the UK's largest research cohort of adult twins. A total of 102 respondents (mean age of 68 years, mean BMI of 25) were case–control matched to measure differences in microbiome composition (16S rRNA gene metabarcoding) as well as muscle mass and strength (measures of sarcopenia).

The results indicate that individuals with a poor appetite had reduced species richness and diversity, in particular reduction of Lachnospira. Furthermore, the results reveal a reduction in muscle strength for individuals with a poor appetite, compared with those with a good appetite.

This is the first demonstration of a difference in composition of the gut microbiome between older individuals with good and poor appetite.

The associations require further examination to understand causality and mechanisms of interaction, to inform potential strategies targeting the gut microbiota as a novel intervention for anorexia of ageing and sarcopenia.

Study

TwinsUK is a cohort that was started in 1992 and now incorporates approximately 14,000 community dwelling twins, who are predominantly female (82%).

The online questionnaire was distributed to 2183 individuals aged over 65, of which 1494 returned responses (68.4%) and 757 had existing microbiota data. This resulted in 102 cases with an appetite score (measured by Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire (SNAQ)) of less than 14, which were matched to controls with a SNAQ score of more than 14. Matched controls were: body mass index, gender, age, diet, calorie consumption, frailty, antibiotic use, socio‐economic status, and technical variables.

Species abundance and diversity, compositional differences, and paired differences in taxa abundance were compared between cases and controls. Muscle mass was assessed by dual‐energy X‐ray absorptiometry and muscle strength was assessed using chair stand time.

Cyclical relationship

While shifts in microbiota composition could simply still be reflective of the overall reduced health, and/or reduced fibre intake in cases compared with controls, the fact that the authors found striking difference in microbiota with appetite after carefully matching on health status and diet would suggest further investigation of a potentially causal relationship.

The observed changes in the gut microbiota in the analysis were from samples pre‐dating the appetite assessment by up to 8 years. This raises the possibility that disturbed host–microbiota functioning is implicated in appetite loss.

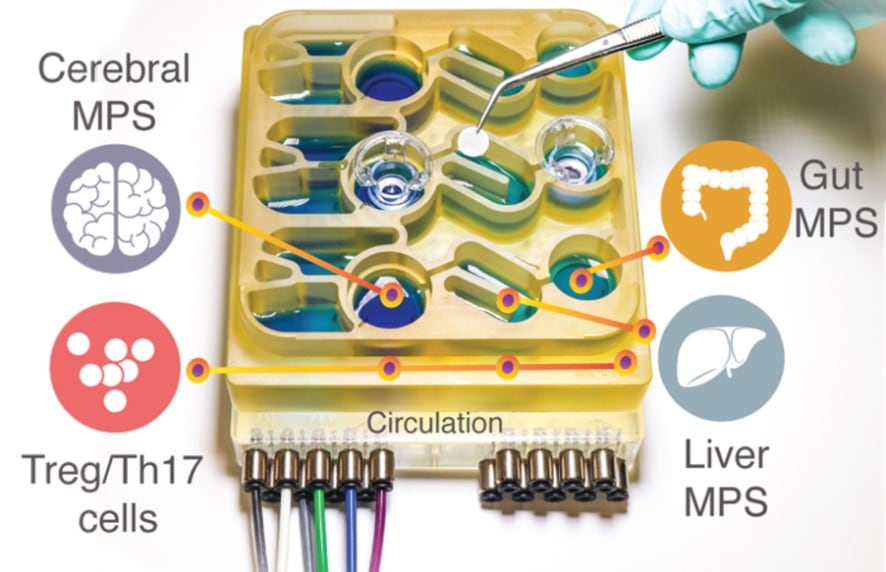

The report explains: "Indeed, the modification of gut hormone secretion by bacteria, including glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1), peptide YY, leptin and ghrelin, suggests the mechanism could be via disruptive bacterial signals in these key neuroendocrine interactions.

"Particularly, alterations in circulating levels of GLP‐1, peptide YY, and Ghrelin have been observed in older individuals. On the other hand, changes to appetite in older individuals may be influencing dietary consumption, further impacting on the observed differences in overall community composition and microbial abundances in the microbiome.

"Certainly, gut microbiota diversity has previously been associated with both healthy and a varied diet. Therefore, there may be a potentially cyclical relationship between microbiome alterations and the development of ill‐health over time, with loss of appetite leading to altered gut microbiota, leading to disturbed microbiota–host interaction, leading to loss of appetite and so on."

The authors note limitations of this study include the largely female sample and the use of self‐reported questionnaires to derive measures of frailty and diet, as well as the lack of detailed information on medications other than antibiotic use. Also, the 16S rRNA metabarcoding rather than full metagenomic analysis, gave a less comprehensive view of microbiota profile.

Source: Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle

Steves. C. J., et al

"The composition of the gut microbiome differs among community dwelling older people with good and poor appetite"